Blogs, Insights

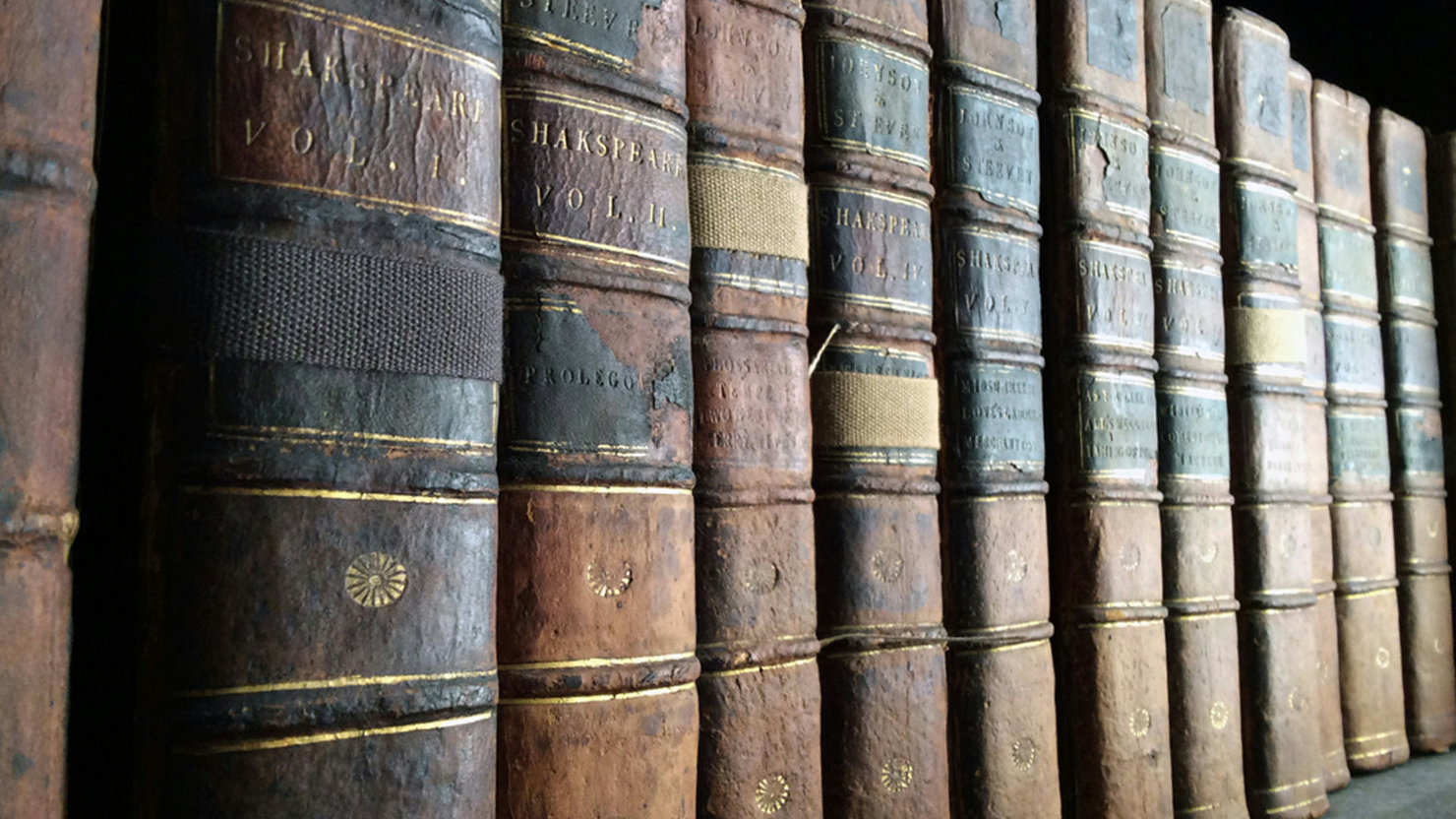

The Shakespeare effect – How ‘the Bard’ shaped the English language

By Jim Smith, Senior Account Executive

Words are very much the tool of the trade for PR and communications. After all, one of our mottos at Farrer Kane & Co is that ‘we make words work’. But actually setting words to work isn’t always straightforward. Writing can be rather like a puzzle, and it can take a few different combinations and drafts before it clicks. Which is one of the reasons (along with the succession of timeless plays he wrote) we should be particularly grateful to William Shakespeare.

Shakespeare’s writing is not always immediately the easiest to understand when it first confronts you in secondary school – the metre and rhythm of speech having evolved considerably over the course of the last five centuries. But despite that, many of the words we use unthinkingly today were actually first created by Shakespeare.

In total, Shakespeare is thought to have invented as many as 594 words as well as a host of idioms and phrases. Some such as ‘hoist with his own petard’ or ‘jealousy is the green-eyed monster’ might be familiar but used only rarely, but if you have ever said ‘uncomfortable’, ‘fashionable’ or ‘eventful’ then you have Shakespeare to thank.

The Shakespearean approach

Shakespeare’s approach to creating new words wasn’t typically a matter of pure invention. That is, he wasn’t in the business of creating new words just for the sake of it when the original was already perfectly sufficient. A number of the words that Shakespeare ‘invented’ had been used before, either in a different language – for instance ‘Manager’ – or in English but with a slightly different meaning.

In fact, in some respects it might be better to understand Shakespeare as more of an editor than an inventor when it comes to the English language. But it is arguably a mark of his genius that he was able to bend existing words to a new meaning, for example by using prefixes and suffixes.

This also often had the added advantage of ensuring that his lines worked in iambic pentameter – which required each line to be 10 syllables long. That was no doubt a particularly valuable skill for a playwright trying to keep up with the insatiable desire of 17th century audiences for new plays.

Although the English language continues to evolve year on year, it’s not quite as straightforward to ‘invent’ new words as it was in Jacobean times. I certainly can’t say that I have ever managed to create a new word whilst editing an article for a client and, happily, a journalist has yet to ask me to pitch in iambic pentameter.

But often enough, trying to find the more creative route to expressing something, be that through a dash of poetry or a more theatrical turn of phrase, ends up elevating copy.

So where we can, why not reach for the more exciting. Why shouldn’t a turbine be powered by a gale instead of just wind? Why not compare financial deregulation to the old Wild West?

We are trying to make words work after all and I have found more times than I can count that the right turn of phrase or even just the right word in the right place can make all the difference. Not all of that can be attributed to liberally borrowing from the ‘Bard’, but it certainly never hurts to have some extra options at your disposal.